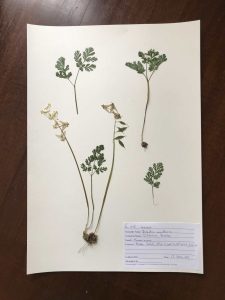

herbarium sample 1

Trout lily sample

Growing our Library of Botanical Knowledge

Written By: Grace van Kan

Date Published: September 6, 2023

Grace van Kan

Clear scientific data is crucial in restoring and protecting land—especially data about a site’s plant life. Just as E. Lucy Braun collected and pressed plants in her botanical studies, our field team collects specimens to document plant communities.

The project began to take shape when Butler University’s Friesner Herbarium donated five cabinets to CILTI. These cabinets are housed in the Daugherty House at Oliver’s Woods. Here we have devoted one wing of the house specifically to our herbarium, a collection of dried plants that are systematically arranged for reference. Our herbarium serves as an ever-expanding repository of plant information.

Grace collecting in the field

An herbarium offers a time-honored way of preserving both plants and botanical knowledge. For centuries, people have collected plant specimens, mounted them on rigid paper, and filed them in cabinets where they can be used as a catalog of local flora. Herbaria can even help us learn more about climate change, conservation, and habitat loss, as larger, older collections can contain specimens that don’t exist anymore.

We can reference and potentially contribute to the Consortium of Midwest Herbaria, a massive digital herbarium. Through observation and research like DNA testing, it’s possible to see similarities and changes in plants from the very same places where E. Lucy Braun collected some of her specimens.

Many of CILTI’s specimens come straight out of Oliver’s Woods—but some are collected farther afield. CILTI has received a research and collecting permit from the DNR Division of Nature Preserves. This specific permit grants the stewardship team permission, with special conditions, to remove specimens from all of CILTI’s state-dedicated nature preserves. The permit is very important and we would not be able to collect from dedicated preserves without it, as it is illegal to remove anything from a state-dedicated nature preserve.

Preserving the specimens involves collecting, identifying, pressing, and mounting plant material.

Sometimes people use plastic bags, pencil boxes, and lunch tins to collect specimens. One tool is made specially for the collection of vascular plants: a vasculum. A vasculum helps maintain the plant in a cool, humid environment until it can be pressed. Typically it is a flattened cylindrical metal case with a lengthwise opening.

Dutchman’s breeches

When identifying a specimen, the stewardship team will include information like the coordinates, habitat type, and nearby plants. On the mounting sheet, they will label the specimen with the plant’s collection number, scientific name, common name(s), family, date, and names of the people who collected and officially identified the plant.

Pressing can take the form of a “sandwich” of cardboard and paper held tightly together with straps to flatten and dry the collected plant. You can buy a plant press whose dimensions are slightly larger than an official mounting sheet. The standard U.S. herbarium sheet is 11 ¾ by 16 ½ inches, made of acid-free paper. In a pinch, you can even press plants in the pages of a heavy book and leave them there to dry.

The entire process is educational because it requires looking closely at plants’ features and behaviors. The herbarium promises to be a key teaching tool for understanding native and invasive plant species.

This growing library of knowledge will inform conservation efforts now and into the future, just as E. Lucy Braun’s specimens are still an invaluable resource nearly a century later.

Ben Valentine

Guest Blogger

Ben Valentine is a founding member of the Friends of Marott Woods Nature Preserve and is active in several other conservation organizations. He leads a series of NUVO interviews with Indiana's environmental leaders, and he cherishes showing his son all the wonders of nature he grew up loving.

DJ Connors

Guest Blogger

DJ Connors, a Central Indiana native and late-to-life hunter, combines a lifelong appreciation for wildlife and the outdoors with a deep passion for exploring the natural beauty of the area he has called home for most of his life. As a husband and father of three, he is committed to ensuring his children have the same opportunities to connect with nature and appreciate the outdoors in their community. DJ’s unique journey into hunting emphasizes sustainability, responsible stewardship, and the importance of preserving these experiences for future generations.

Bridget Walls

Guest Blogger

Bridget is our first ever Communications and Outreach Intern. She is a graduate of Marian University, where she combined English, studio art, and environmental sciences in her degree studies. As treasurer for Just Earth, the university's environmental club, she helped plan events encouraging a responsible relationship between people, nature, and animals.

Jordan England

Guest Blogger

Jordan England is a lifelong Shelby County resident who graduated from Waldron Jr. Sr. High School (just a few miles from Meltzer Woods!). After earning her B.S. degree in Retail Management from Purdue University, she returned to Waldron to start a family with her husband, Brian. Together they have 3 young children and enjoy sharing with them their love of the community. Jordan is the Grants and Nonprofit Relations Director at Blue River Community Foundation, managing BRCF’s grant program, providing support to local nonprofits, and promoting catalytic philanthropy in Shelby County.

Cliff Chapman

President and CEO

As CILTI’s President and CEO, Cliff keeps CILTI’s focus on good science and stewardship. He’s mindful that the natural places you love took thousands of years to evolve and could be destroyed in a single day, and that knowledge drives his dedication to their protection.

Stacy Cachules

Chief Operating Officer

Among her many key duties as Assistant Director, Stacy has the critical task of tracking our budget, making sure we channel donations for maximum efficiency. When her workday’s done, Stacy loves to spend time with her two young boys—and when not traveling, she’s likely planning the next travel adventure.

Ryan Fuhrmann

Vice Chair

Ryan C. Fuhrmann, CFA, is President and founder of Fuhrmann Capital LLC, an Indiana-based investment management firm focused on portfolio management. Ryan’s interest in land conservation centers around a desire to help preserve natural habitats for wildlife and the subsequent benefits it brings to people and the environment.

Joanna Nixon

Board Member

Joanna Nixon is the owner of Nixon Consulting, an Indianapolis-based strategy and project management firm focused on the nonprofit sector. She currently serves as the Philanthropic Advisor for the Efroymson Family Fund. Prior to opening her consulting practice in 2000, Joanna was vice-president for grantmaking at Central Indiana Community Foundation (CICF). Joanna has more than 25 years of experience in the nonprofit and arts and culture sector. She is passionate about the environment and loves bringing big ideas to life and creating high-quality arts and culture programs and experiences. Joanna enjoys outdoor adventures, including competing in fitness obstacle course races and hiking with her high energy Australian Cattle Dog, Jackson.

Karen Wade

Board Member

Before retiring, CILTI board member Karen Wade worked for Eli Lilly & Co. In retirement she volunteers for a number of organizations, including the Indiana Master Naturalist program, Johnson County Native Plant Partnership CISMA, Meadowstone Therapeutic Riding Center, and Leadership Johnson County.

David Barickman

Development Systems Manager

Born and raised in Central Illinois, David spent many days as a child wandering around the river, forest and lakes there. He works behind the scenes as a key member of our fundraising team. When not working, David loves to be outdoors hiking, fly fishing, kayaking or woodworking.

Jamison Hutchins

Stewardship Director

Jamison leads our stewardship team in caring for the land that is so important to you. He comes to our team after eight years as Bicycle and Pedestrian Coordinator for the city of Indianapolis, where his work had a positive impact from both health and environmental perspectives.

Jen Schmits Thomas

Media Relations

An award-winning communicator and recognized leader in Central Indiana’s public relations community, Jen helps us tell our story in the media. She is the founder of JTPR, which she and her husband John Thomas own together. She is accredited in public relations (APR) from the Public Relations Society of America, and loves to camp and hike in perfect weather conditions.

Shawndra Miller

Communications Director

Shawndra’s earliest writing projects centered around the natural world, starting when a bird inspired her to write her first “book” in elementary school. Now she is in charge of sharing our story and connecting you to our work. Through our print and online materials, she hopes to inspire your participation in protecting special places for future generations.

Phillip Weldy

Stewardship Specialist

Phillip enjoys nature’s wonders from an up-close-and-personal perspective as he works to restore the natural places you love. As an AmeriCorps member in Asheville, NC, he had his first full immersion in relatively undisturbed land while reconstructing wilderness trails in National Parks and National Forests.

December 11, 2025

Brown County is beloved for its vistas of iconic Southern Indiana hills. Now the forests under protection in the county include another 89 acres. That’s all thanks to our members’ generosity!

Betley Woods,Blossom Hollow,Callon Hollow,Newsroom,Properties

December 9, 2025

Board member Ryan C. Fuhrmann, CFA, is President and founder of Fuhrmann Capital LLC, an Indiana-based investment management firm. As our incoming board chair, Ryan brings a strong desire to preserve natural habitats for wildlife. We asked him to share his perspective on making gifts of stock to the [...]

Newsroom

December 2, 2025

Our board member, John Bacone, reflects on conserving key natural areas. He led the Department of Natural Resources Division of Nature Preserves for over four decades. Years ago, when I was working in the Indiana DNR Division of Nature Preserves (DNP), I asked Bob Waltz, the State Entomologist, how [...]

Betley Woods,Blossom Hollow,Homepage,Meltzer Woods,Newsroom,Properties,Stewardship